References

- Sebastiani G, et al. Current considerations for clinical management and care of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Insights from the 1st International Workshop of the Canadian NASH Network (CanNASH). Canadian Liver Journal. 2022;5(1):61-90.

- Povsic M, et al. A Structured Literature Review of the Epidemiology and Disease Burden of Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH). Advances in Therapy. 2019;36(7):1574-1594.

- Rinella ME, et al. AASLD Practice Guidance on the clinical assessment and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2023;77(5):1797-1835.

- Cameron JL, et al. Current surgical therapy. 14th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023.

- Rinella ME, et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology. 2023;78(6):1966-1986.

- Younossi Z, et al. The burden of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: A systematic review of health-related quality of life and patient-reported outcomes. JHEP Rep. 2022;4(9):100525.

- Romero-Gomez M. NAFLD and NASH: Biomarkers in Detection, Diagnosis and Monitoring. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020.

- Ng CH, et al. Mortality Outcomes by Fibrosis Stage in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(4):931-939.e935.

- Loomba R, et al. The 20% Rule of NASH Progression: The Natural History of Advanced Fibrosis and Cirrhosis Caused by NASH. Hepatology. 2019;70(6):1885-1888.

- Kleiner DE, et al. Association of Histologic Disease Activity With Progression of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1912565.

- Sandireddy R, et al. Systemic impacts of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) on heart, muscle, and kidney related diseases. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2024;12.

- Sanyal AJ, et al. Cardiovascular disease in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis compared with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and other liver diseases: A systematic review. Am Heart J Plus. 2024;41:100386.

- Muthiah MD, et al. A clinical overview of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A guide to diagnosis, the clinical features, and complications-What the non-specialist needs to know. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022;24 Suppl 2:3-14.

- Quek J, et al. Global prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in the overweight and obese population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8(1):20-30.

- Younossi ZM. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease - A global public health perspective. J Hepatol. 2019;70(3):531-544.

- Diabetes Canada. New Clinical Practice Guidelines Released for MASLD. 2025. Available at: https://www.diabetes.ca/media-room/news/new-clinical-practice-guidelines-released-for-masl. Retrieved August 12, 2025.

- Kim J, et al. Diabetes and Metabolic Dysfunction-associated Steatotic Liver Disease in Adults: A Clinical Practice Guideline. Can J Diabetes. 2025;49(4):222-236.

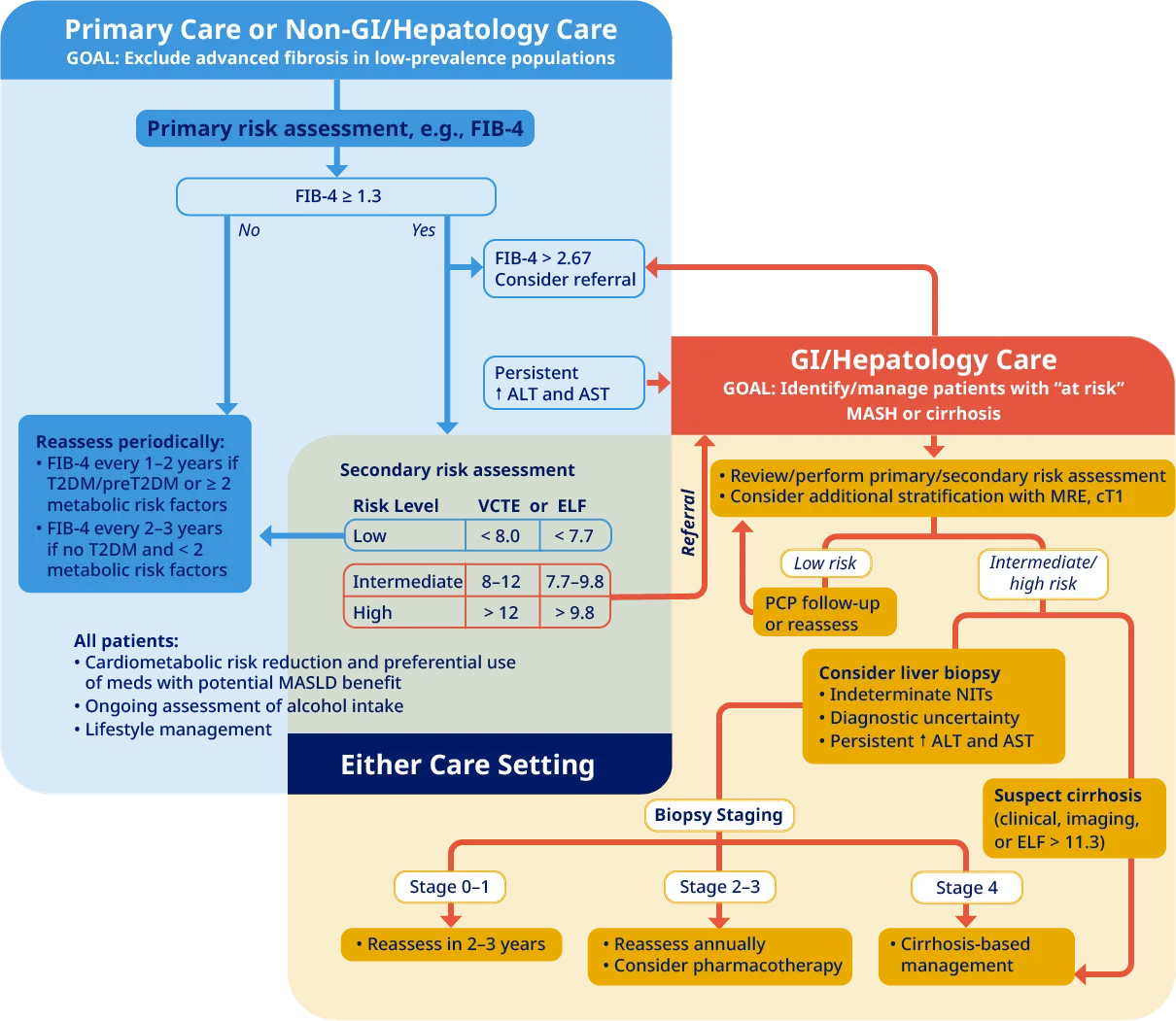

AASLD, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases;

ALT, alanine aminotransferase;

AST, aspartate aminotransferase;

CKD, chronic kidney disease;

cT1, corrected T1;

CVD, cardiovascular disease;

ELF, Enhanced Liver Fibrosis;

FAST, FibroScan-AST;

FIB-4, fibrosis-4 index;

MAST, score derived from MRI-PDFF, MRE, and serum AST;

MRE, magnetic resonance elastography;

NIT, noninvasive test;

PCP, primary care provider;

PDFF, proton density fat fraction;

T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus;

VCTE, vibration-controlled elastography.

All trademarks and registered trademarks are the property of their respective owners.

Apis Bull Design® is a registered trademark of Novo Nordisk A/S used under licence by Novo Nordisk Canada Inc.

Novo Nordisk Canada Inc., tel: (905) 629-4222 or 1-800-465-4334.

© Novo Nordisk Canada Inc.